Despite recording 28 years of uninterrupted growth, it was already clear prior to the coronavirus pandemic that Australia’s economy was not working for everyone. In the last 20 years, manufacturing, as a percentage of GDP declined from 12% to 6%. Steel production has almost halved, and in the last five years, Holden, Ford and Toyota shut their Australian production.

These trends reflect the impact of globalisation and free trade, with industrial activity moving offshore and Australia’s economy becoming increasingly reliant on service industries like tourism, education, and finance & professional services. Australia is not alone in the changes we have observed over the past few decades. The share of GDP going to workers in the form of wages has declined in most of the developed world. Meanwhile, the portion of GDP going to corporate profits has rocketed.

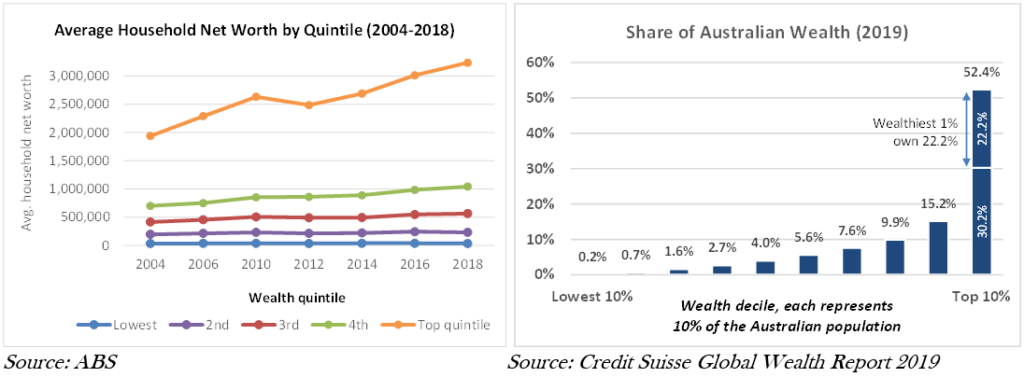

The economist Thomas Piketty (2013) argues that under neoliberal economic policies, those who make money from investment income have higher earnings capacity than workers who earn a salary. As a result, the rich get richer and the poor are locked out of participating in growth. We see this trend in Australia, with the evolution of wealth over the last 15 years resulting in severe wealth inequality (this is as far back as the ABS data goes). According to Credit Suisse, as of 2019, the bottom 10% of Australians owned 0.2% of all wealth, while the top 10% owned 52.4%.

It is one thing to have a high level of inequality, but it is another that it is getting worse. Now, the pandemic and associated lockdowns are disproportionately impacting young, low-income Australians. These are generally the same groups who were not able to participate in Australia’s economic growth ‘miracle’.

Adding to the failure of neoliberal economic policies, COVID is fast-forwarding the shift to automation, further reducing the bargaining power of workers. In economic terms, automation leads to a reduction in operating costs and an increase in fixed/capital costs. This new cost structure results in economies of scale which lead to the emergence of monopolies. The FAANG companies (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google) are prime examples, but this phenomenon is not restricted to the tech sector. Mergers and acquisitions by global firms have resulted in a lessening of competition in the last 20 years. Simultaneously there has been a rise in corporate profit-shifting and tax evasion, as executives justify this as part of their ‘fiduciary duty’ to shareholders.

……. the system is producing self-reinforcing spirals up for the haves and down for the have-nots.

Ray Dalio, the founder of the world’s largest hedge fund, Bridgewater Associates describing the impact of these factors

In such a system, it is reasonable that a fair tax system would be progressive and would tax capital at a higher rate than wage income, because capital has higher earnings capacity.

Not only is this approach fair, it is also efficient. The evidence suggests that higher tax rates on the highest levels of income and wealth will not deter growth. The next generation of entrepreneurs like Atlassian co-founders Mike Cannon-Brookes and Scott Farquhar (whose self-confessed goals were “to make $35,000 a year and not have to wear a suit”) aren’t likely to be concerned with the tax rate they pay on each dollar they earn above the first 50 million. Depending on Atlassian’s share price on any given day, its co-founders each hold about US$12 billion in wealth.

This leads us to query the purpose of our economy, something that as far as we are aware hasn’t been addressed by the major parties. Without articulated purposes, the economy will only benefit those with vested interests, to the detriment of everyone else. While this is only a starting point, we propose the following basic purposes of the economy as a guide:

Our economy must be robust, efficient, and effective and must;

- maintain high standards of living

- ensure a fair distribution of wealth,

- be a stable environment for business and manufacturing

- foster worthwhile employment and excellent services,

- and do all this whilst conserving natural assets for future generations.

Above all, economic levers must be transparently based on evidence.

We must move away from focusing on aggregate GDP, which ignores how economic gains are distributed as well as impacts on the environment. RBA Governor Philip Lowe has noted we need policy that focuses on standards of living and not simply adding more people to make the economy look bigger.

Focusing on GDP leads to a short-term approach that is not desirable if we care about the quality of life of future generations, or for those of us who will live longer than a few more decades. It will lead to an increasingly scorched earth, with more intense bushfires, water scarcity, and coral bleaching. And ultimately, it will destroy our economy too.

We must re-evaluate both sides of the fiscal equation, taxation (how government raises revenue) and expenditure (what government spends on and how effectively this is spent). And we must ensure the appropriate policies are in place to regulate businesses.

To prompt this reassessment of the purpose of economic policy, we propose that the Government present an annual State of the Economy report providing an update on Australia’s performance on key economic indicators. The report should be no longer than 30 pages and accessible to all Australians, not just policy professionals.

The report should include indicators illustrating the state of Australia’s economy, such as:

| measure | proposed metric |

|---|---|

| Economic well-being | Personal income |

| Wealth inequality | Household net worth |

| Employment | Unemployment and under-utilisation rates |

| Quality of government | Breakdown of government taxation and expenditure |

| Financial system stability | Household debt-to-income |