Now we have the figures. In 2020 >3 million people withdrew $36.4 billion from their superannuation accounts.

No doubt it was a popular life-saver for almost ten per cent of the population during Covid lockdowns. However, it was likely driven less by compassion for people who could not afford their rent than by the Liberal Party’s longstanding dislike of the growing wealth and power of the industry super funds.

The 12% rate was originally intended to be in place in 2019 and that would deliver retirees roughly 70% of their pre-retirement income. In 2014 that start date was deferred, with the support of the Palmer Party, until July 2021. At the time, Paul Keating said this would lower the average person’s super balance by $100,000.

The McKell Institute says the Covid withdrawal scheme means that for anyone who withdrew the maximum allowable amount ($20k), the investment growth will be, on average, $3,600 less – a $4.71 billion market gain lost.

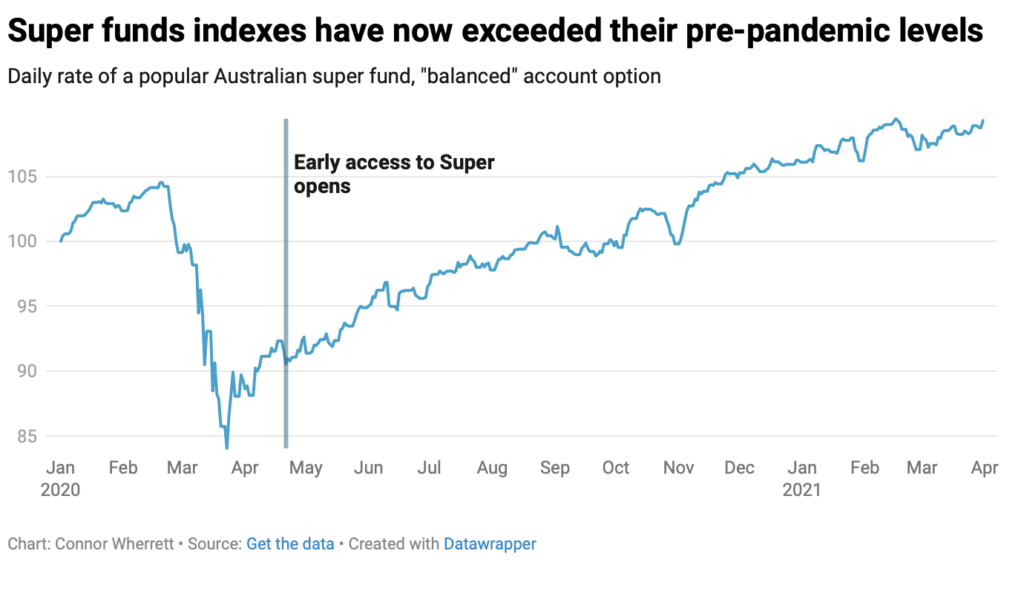

The problem was that during 2020, the stock market was at its lowest point in more than 5 years. The sudden run on funds forced asset sales and, as a result, those who could afford to invest at this low ebb did well when the economy bounced back, ie. the rich got richer and the poor, whilst temporarily better off, will pay for it in retirement.

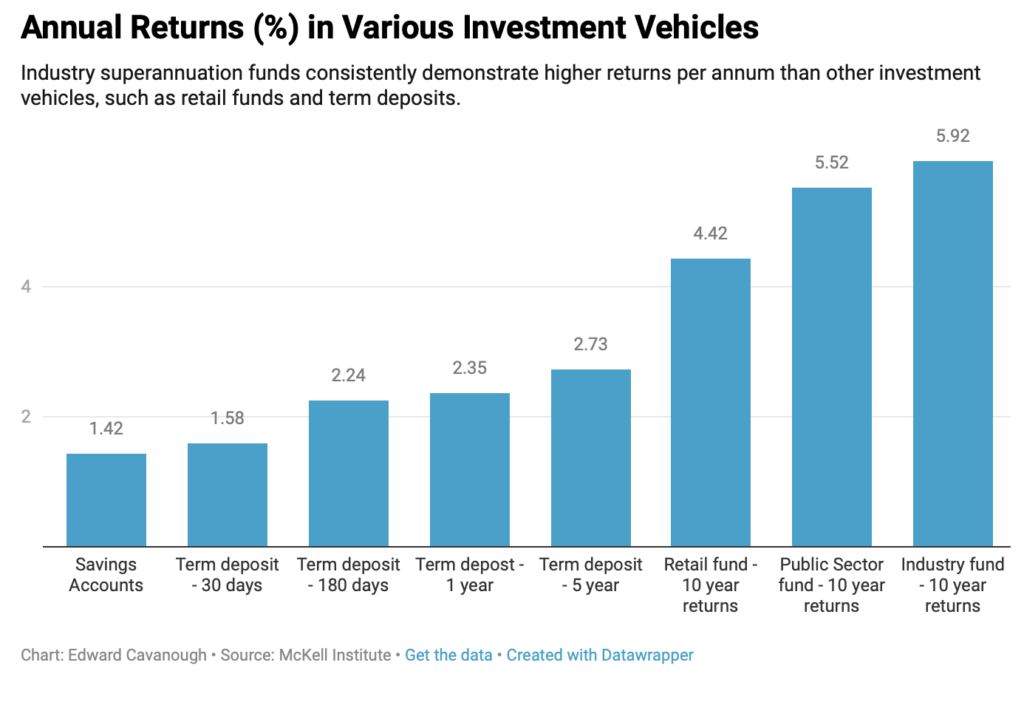

McKell says one of the biggest long-term risks of this scheme is that it starts to treat superannuation accounts like regular bank accounts that can be drawn upon when there’s an economic crisis. And the more like a bank account our super is, the lower the returns long term.

It’s easy to see why this private-enterprise-leaning government is keen to undermine the public sector and industry funds – they outcompete the private retail funds, operated largely by the banks, by a country mile.

And, BTW, how are those banking reforms going?

Last month legislation lifted super contributions to 10% and the $450 minimum threshold was removed which will benefit ~300,000 people – 3 per cent of employees – mainly women, young, lower-income, and part-time workers. In a very small way, this will benefit women.

The legislation also increases superannuation contributions by half a percent a year, reaching 12 percent by 2025. All good but women taking time out for caring and generally receiving lower wages than men means the super gender gap has still not been fixed.