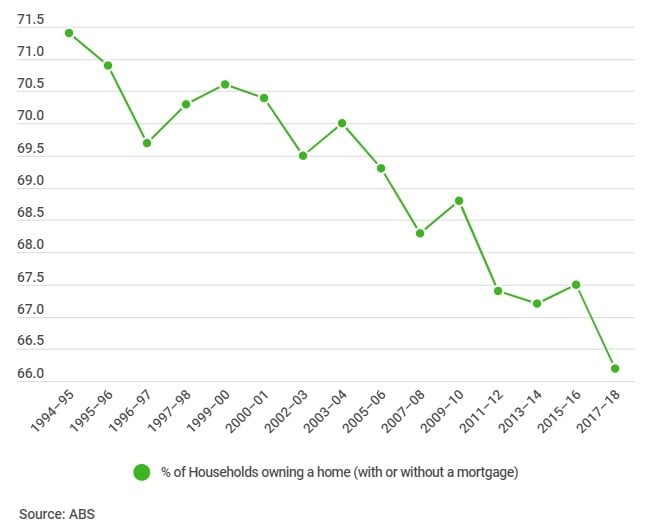

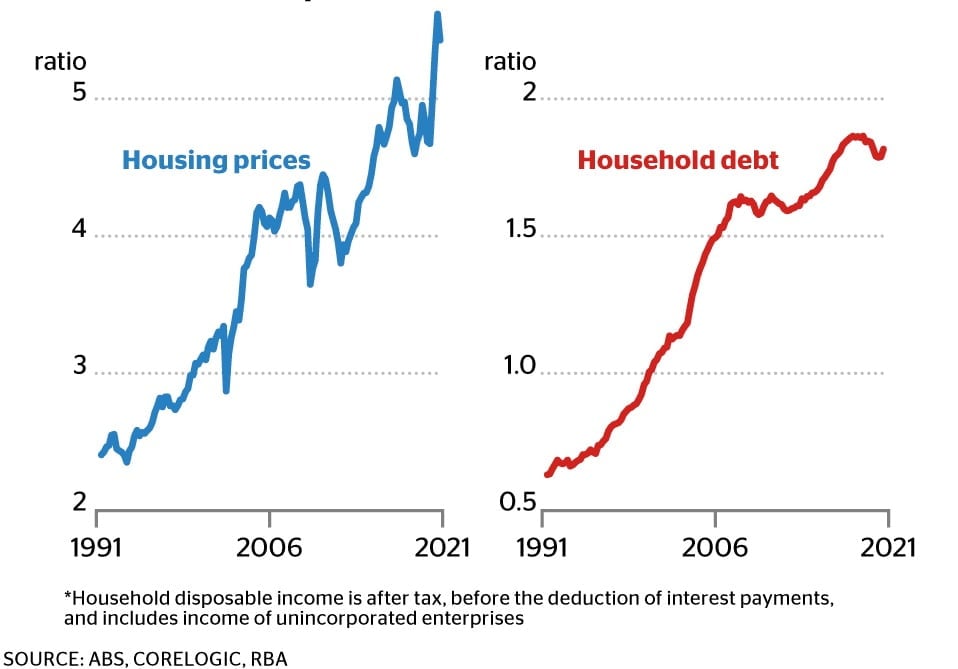

House prices are spiralling out of control, affordable housing is scarce and there are over 478,000 low and very low-income households across Australia in unaffordable rental housing. 100,000 Australians are homeless, 430,000 are on waiting lists for public housing.

This is the result of:

- the absence of a forward-thinking, long term national plan for housing

- a 20-year decline in government investment in social public, and community housing

- Commonwealth rent assistance that has not kept pace with rental increases

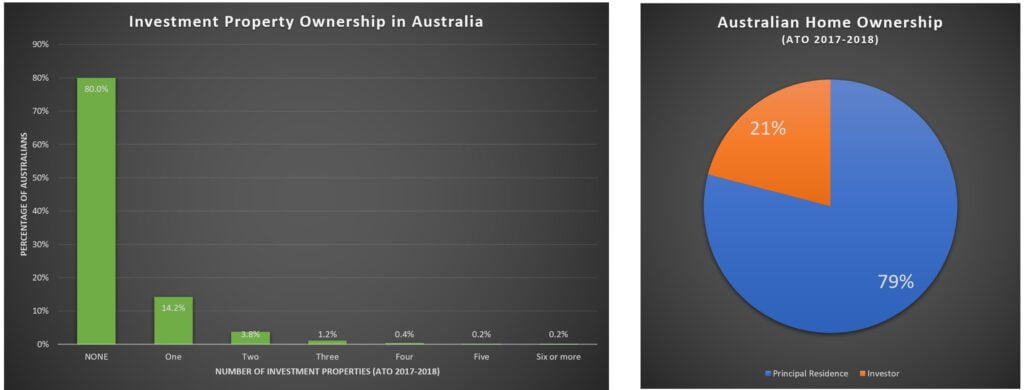

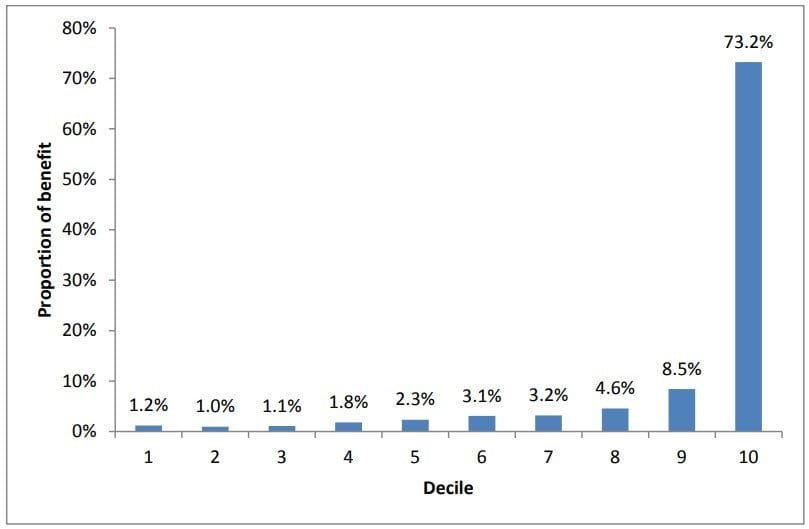

- tax laws that favour the wealthy and encourage speculation on ongoing increases in house values

- handouts and subsidies, mostly for first home buyers, that distort and inflate prices

- inadequate prudential standards that encourage buyers to borrow ever-higher sums on low deposits assuming interest rates will remain low

- recent government encouragement for people to use their super to buy homes which pumps up prices while draining super fund accounts.

Our objectives

- Enough new housing to meet Australia’s needs

- Housing that is affordable for renters and home buyers on low to moderate incomes

- Stabilise or reduce house prices

Our plan

- Fund 100,000 new affordable and 100,000 new social and community housing units

- Transfer 50% of public housing stock to community-based housing operators

- Fund safe, permanent and supported housing, no strings attached, for people who have been homeless, medium to long term

- Ensure that 10 percent of the

- Change negative gearing rules to only apply to investment in new housing

- Halve the capital gains tax exemption to discourage speculation on existing housing and long-term house vacancies, currently ~4%

- Discourage investment in housing by self-managed super funds

3. Loan caps

- Introduce sufficient loan caps to prevent real increases in house prices and excessive indebtedness by real estate buyers. A lower cap would apply to investors than first home buyers.

- Develop a long-term national plan for housing

- Reform residential tenancy regulations through the current NHHA to end unfair evictions and tie rent increases to increases in the median wage

Our plan in detail

Background

References

National Affordable Housing website (A not-for-profit social value enterprise to lobby for more affordable housing options in Australia.)

- National Shelter (A non-government organisation that aims to improve housing access, affordability, appropriateness, safety and security for people on low incomes.)

- Negative gearing cost reaches $13 billion a year (Sydney Morning Herald, 2020)

- Fact check: Did abolishing negative gearing push up rents? (ABC, 2016)

- Australian home ownership & tenancy (Dominic Beattie, Savings.com.au)

- How a millionaire pays no income tax (The Age, 2019)

- If we realised the true cost of homelessness, we’d fix it overnight (The Conversation, Sep 2020)

- Australia needs to triple its social housing by 2036. (The Conversation,2018)

- Who really benefits from negative gearing? (Australia Institute, 2018)

- How negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount benefit the top 10 per cent and drive up house prices. (Australia Institute, 2015)

- Reform of the personal income tax system (ACOSS, 2009 )

- Liberal senator backs redeploying of superannuation early access scheme (The Age, April 2021)

- Sydney and Melbourne house prices rise tens of thousands of dollars in one month (The Age, April 2021)

- Let’s make renting fair (rentingfair.org.au)

- Homelessness and housing (Australian Human Rights Commission)

- Implementation of the National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness (Australian National Audit Office, May 2013)

- Homelessness statistics (Homelessness Australia)

- Housing affordability: Rise of Bank of Mum and Dad fuels inequality in hot market (Domain, April 2021)

- National Plan for Affordable Housing (PDF, Community Housing Industry Association)

- Victoria’s Big Housing Build (Victorian government initiative to build 12,000 homes)

- City of Melbourne Affordable Housing Plan

- AHURI analysis on housing, homelessness and domestic and family violence

- Treasury estimates that the capital gains tax discount cost $10.6 billion in lost revenue in 2018/19 (as stated in Treasury’s Tax Benchmarks and Variations Statement 2020, E15).

- We need a top-level inquiry into runaway home prices – and Ken Henry’s up for it (The Age, August 2021)

- Melbourne houses climb $457 a day amid fears of living standard hit – “Ponzi Scheme” (The Age, September 2021)

- Lending restrictions need to be considered (SMH, September 2021)

- APRA’s moves to cool housing could end banks’ golden run (AFR, April 2021)

- To fix Australia’s housing affordability crisis, negative gearing must go (The Conversation, April 2021)

- Value of macro-prudential reforms such as loan caps (ABC, September 2021)

- Time for a crackdown on ‘liar loans’ to douse home price bonfire (Jessica Irvine, The Age, Oct 2021)

- APRA tightens home loan standards for new customers as risks grow (The Age, Oct 2021)

- How do you raise mortgage rates without actually raising them? (Guardian, Greg Jericho)

- Now it’s Liberals telling us we are going to have to cut the CGT concession (The Conversation, By Peter Martin, Oct 2021)

- One graph that shows why it’s harder for Millennials to buy a house (Elizabeth Redman, The Age, Dec 2021)

- Rate rises may slow housing market but no affordability improvement in sight (The Age, Jan 2022)

- Investor with 8000 homes calls for negative gearing to be axed (The Age, Feb 2022)

- Fairer housing should mean those who have, help those who have not (The Age, Mar 2022)

- ‘It’s all going up’: Workers face rental stress in key marginal seats (The Age, Mar 2022)

- ‘Pure electioneering’: First-home buyer help will increase property prices, experts warn (Domain, Mar 2022)

- Why the rental housing crisis gripping Australia is NOT going to end anytime soon (Daily Mail Australia, Mar 2022)

- ‘Housing in Australia is broken’: only 1.6% of private rentals are affordable for those on minimum wage (Guardian, Apr 2022)

- New policies barely lighten the load when it comes to affording a home (The Age, May 2022)

- Negative gearing and capital gains tax breaks go to top income earners and men (Domain, May 2022)

- ‘I’ve never felt this vulnerable’: Guardian readers share their rental crisis horror stories (Guardian, May 2022)