The fairest, most effective way to reduce cost of living pressures for those who need it most is to abolish the lowest income tax bracket. Those on such low incomes have been particularly hard hit by big increases in grocery, energy, transport, and child and aged care prices.

Former head of the Australian Consumer and Competition Commission, Allan Fels, found inflation, questionable pricing practices, a lack of price transparency and regulation, a lack of market competition, supply chain problems and unrestricted price setting by retailers were some likely causes.

Here’s what must be done

- Target those in need by abolishing the lowest income tax bracket (which currently levies tax on earnings $18,201 – $45,000 per annum).

- Effectively tax passive capital income by reducing the capital gains tax discount from 50% to 25%

- Introduce a 20% super profits tax on non-renewable resource extraction and use the revenue to transition the national power grid to renewable energy.

- Correct the loss of wages to women in particular who lost twice as many jobs as men during COVID and were much less likely to receive JobKeeper support, compounding women’s lifetime economic disadvantage.

- Adopt Alan Fels’ recommendations to empower the ACCC to investigate, monitor and regulate prices for child and aged care, banking, grocery and food sectors to ensure fair and transparent pricing.

- Develop a mandatory grocery code of conduct for the food and grocery sector and a price register for farmers, protecting them from unfair pricing by major supermarkets and food processors.

Here’s why:

Much has been made of the role of the pandemic and the war in the Ukraine in driving the current cost-of-living crisis. While these factors have exacerbated the crisis, these events are only the latest drivers in what has been a long term trend.

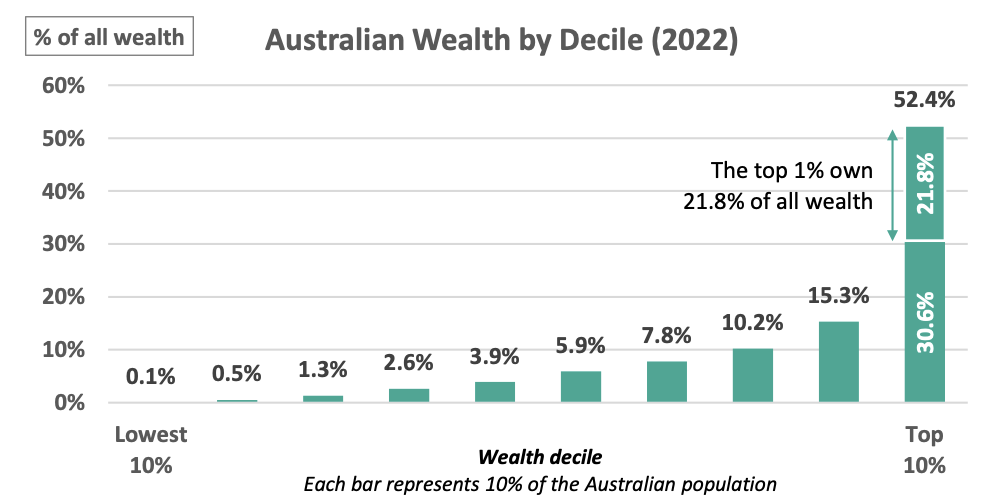

Australian Bureau of Statistics data shows that wealth inequality in Australia has been getting consistently worse over the last 20 years. The most recent snapshot shows that the wealthiest 10% of Australians own 52.4% of all wealth.

Source: UBS 2023 Global Wealth Report

Over the last generation, our economy has been transformed by technology growth and globalization leading to an increase in the role of capital and a decrease in the role of labour.

New technologies (including AI and automation) have led to an increase in fixed business’s costs relative to marginal/operating costs. For example, when Amazon equips a new distribution centre with robotic machinery for sorting and packaging deliveries, it incurs a large upfront cost to build the facility, but from then on, it has low marginal costs for each product it moves through the facility once it is operational. This is different from the economic model of the past, where tasks were manually undertaken by salaried workers, who were considered by the employer to be operating costs.

This new cost structure results in economies of scale which leads to the emergence of natural monopolies. The usual examples are Amazon and the other FAANG companies (Facebook, Apple, Netflix and Google), but this phenomenon is not restricted to the tech sector. We see the same thing with supermarkets, mining companies, airlines, and in many industries across the economy.

In its 2023 economic outlook, the OECD found that corporate profits were a larger factor in driving up inflation than wages.

For the owners of shares in these increasingly large companies, the result is huge dividends and capital gains. For workers on a salary who don’t own a serious share portfolio, the outcome is that wages are increasing at a lower rate than living costs, resulting in a higher cost of living.

This dynamic has been described by Ray Dalio, the founder of one of the world’s most successful investment funds, Bridgewater Associates, who wrote: “the system is producing self-reinforcing spirals up for the haves and down for the have-nots”.

The trend has been exacerbated by globalization, which is associated with a reduction in barriers to trade and investment. The result is internationally-mobile capital that constantly seeking to invest in countries with the lowest labour costs (and environmental and human rights standards). The nature of globalisation is to pour capital into countries with the cheapest labour, and to incentivize countries into a race to the bottom in terms of workers rights, environmental standards and corporate tax rates.

In addition to the inequality drivers described above, it is also the case that in many instances governments have put forward poorly designed policies that have exacerbated the issue by giving handouts to the top end of town.

The most obvious example is the COVID JobKeeper program, which gave away $89 billion of taxpayer money to corporations. While the intent of the program—to help companies keep their employees on during lockdowns—may have been sound, the policy had a giant loophole that meant companies never had to pay the money back.

A number of Australia’s leading economists were on record at the start of the pandemic stating that a program of this kind should use “income-contingent” loans. That is, companies have to pay them back if and when they can. As it turns out, almost all of the companies that received JobKeeper could have paid amounts back, which would have avoided the enormous budgetary hit that the country took during the pandemic.

The Morrison-Frydenberg Government ignored the advice of the experts and unnecessary JobKeeper payments were not returned.

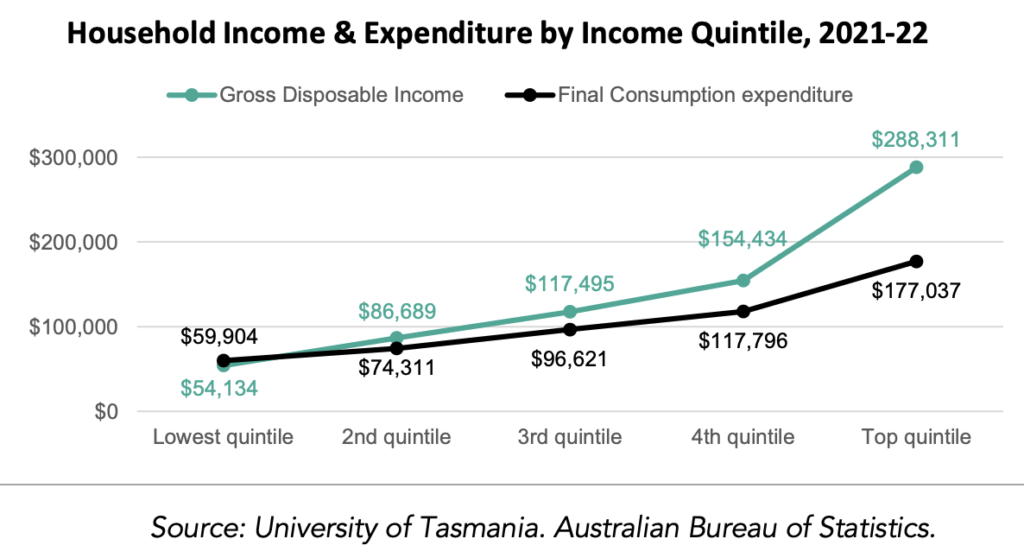

We need to ensure prosperity from technological advancement is shared, not extracted only by the few. This can be achieved by recalibrating our tax system to shift the tax burden to reflect the changes that have occurred in our economy over the last 20 or 30 years. By targeting the lowest income tax bracket, our proposal will give money back to those in need, who really need it. And from a cold hard economic perspective, it will also be good policy, because the lowest 20% of households are the only bracket that spends 100% of every dollar of disposable income they receive.

Source: University of Tasmania. Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Select Committee on Cost of Living. Submission 30. University of Western Australia Economics Department.

Select Committee on Cost of Living. Submission 48. The University of Tasmania Economics Department.

The Conversation. Supermarket Charging Exploitative Prices. February 2024.