Slides from our 11-Dec-2021 climate webinar are available here.

The effects of human-caused global warming are happening now, are irreversible on the timescale of people alive today, and will worsen in the decades to come (NASA).

The world needs to change its approach to energy. We must recognise the limits to endless growth, and find a sustainable balance with our environment.

Climate change is a collective action problem at a global scale. We need the federal government to drive emissions reduction and work toward a global strategy to reduce atmospheric carbon. We will work with the government of the day to enact sound policy.

To reach net-zero by 2050, we must take action in this decade. This is the decisive decade and action taken in the next ten years will define the trajectory to 2050.

It can be done. The reduction targets proposed by the government’s own Climate Change Authority in 2015 were to reduce emissions by 45 to 65 per cent by 2030 (on 2005 levels). The report Pathways to Deep Decarbonisation in 2050 is instructive on how we can achieve this. This is eminently achievable, yet it requires concerted action led by government to drive the transition.

We are demanding this of Government:

- Be honest. Declare a climate emergency

- Commit to reducing emissions by at least 66% by 2030 and develop pathways for this and for net-zero emissions by 2050

- Break it down: target sectors with the biggest emission footprints – electricity, stationary energy, transport and agriculture

- Price carbon for a carbon-constrained world, starting at $30/tonne, to be increased in line with key trading partners

- Stop subsidising the fossil fuel industry – it’s a losing strategy

- Establish a Just Transition Authority charged with planning the transition away from fossil fuels

- Say no to nuclear power – it’s not economic

Read on for the details.

By adopting these measures , we will set Australia on the path to deep decarbonisation, at the same time ensuring we have the right policy settings to ensure a stable transition of our economy.

There is no time to lose.

1. Be honest. Declare a climate emergency

The first demand, and the one that all the other demands lead from, is to tell the truth. A democracy cannot function if people don’t have a common understanding of the truth of what is happening in the world.

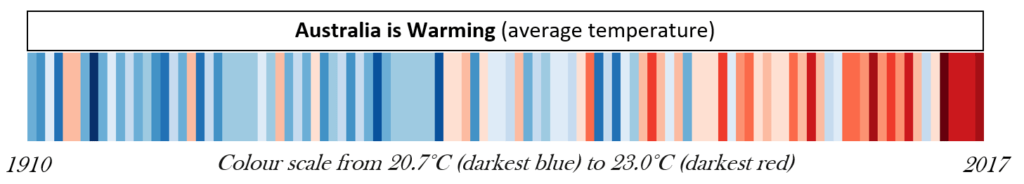

The earth is warming. Australia is warming. Data from the Bureau of Meteorology, shown below using shades of blue and red to represent temperatures below and above the average temperature, suggests that Australia has already warmed by more than 1 degree celsius. The overwhelming evidence is that this warming is due to human activity.

Source: Climate Lab Book visualisation, showing Australian Bureau of Meteorology data.

Australia is not the largest global emitter, but we have a significant role to play, as a developed country and especially as the world’s largest coal exporter.

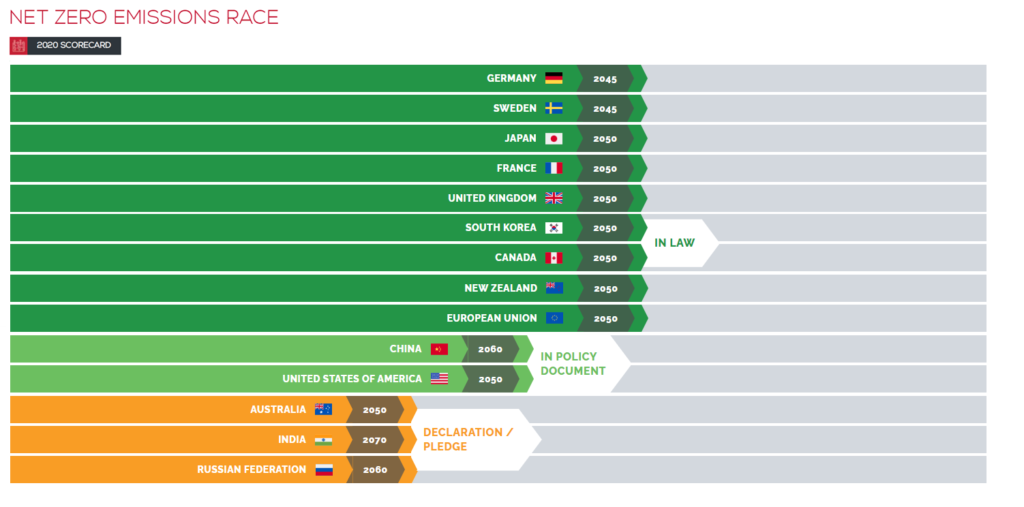

In the last year, many countries have committed to reaching net-zero emissions over the next 20 to 30 years. The Morrison Government joined the fold with a net-zero pledge in the face of pressure leading up to the Glasgow Climate Conference in November 2021.

But unlike most of our developed economy peers, Australia has yet to pass a net-zero commitment in law.

Australia is increasingly a pariah on climate change, dragging our feet when we could be a global leader.

Source: Net Zero Tracker, Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit

2. Develop a pathway to net-zero emissions, targeting key sectors

A net-zero pledge means nothing if action is not taken today to drive the process to actually achieve the pledged reduction in emissions. We need an actionable roadmap to meet our emissions reduction commitments. Australia’s states and many companies and super funds are onboard with this. But this needs to be led by the federal government.

Just like it has been MIA on managing COVID, the federal government needs to step up on climate change.

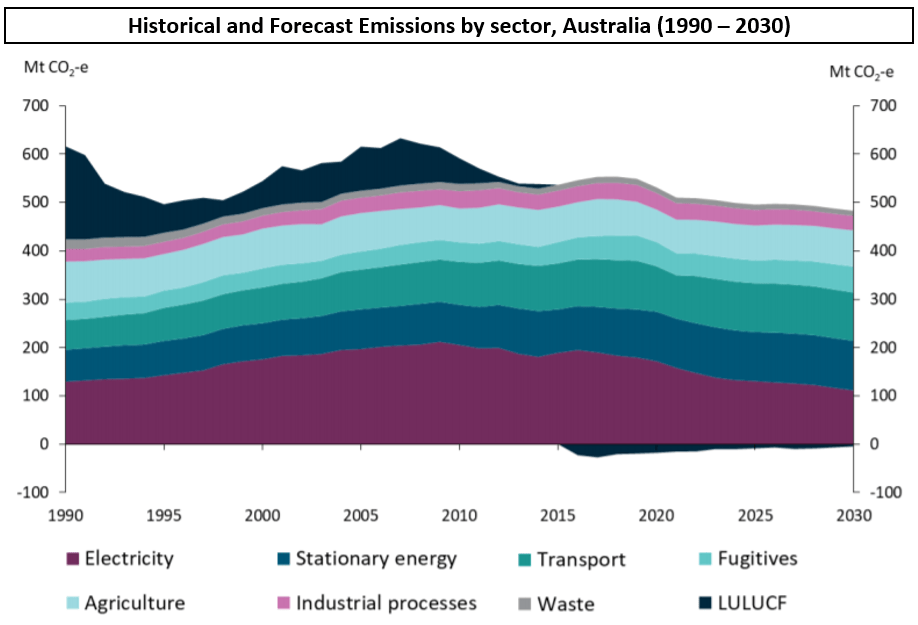

Data from the Department of Industry, Science, Energy & Resources shows that Australia’s emissions have remained pretty consistently at or above 500 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent per annum for the last 30 years.

Source: Department of Industry, Science, Energy & Resources, Australia’s Emissions Projections 2020, Figure 8.

A quick look at the above graph helps explain why the current government prefers to use 2005 as the baseline for its emissions reduction targets. Emissions peaked around that time, mainly due to the contribution from land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) emissions (black on the graph). These land use emissions are notoriously hard to measure, but they elevate the emissions baseline. This accounting trick makes emissions reduction targets with a 2005 baseline sound more ambitious than they really are.

As we can also see from the graph, the biggest contributors to emissions are electricity, stationary energy (things like mining and manufacturing), transport and agriculture. These four segments make up about 80% of emissions. An effective climate policy must target these segments first, reducing emissions and helping to transition workers in carbon-exposed industries that will impacted.

3. Break it down: target sectors with the biggest emissions footprints

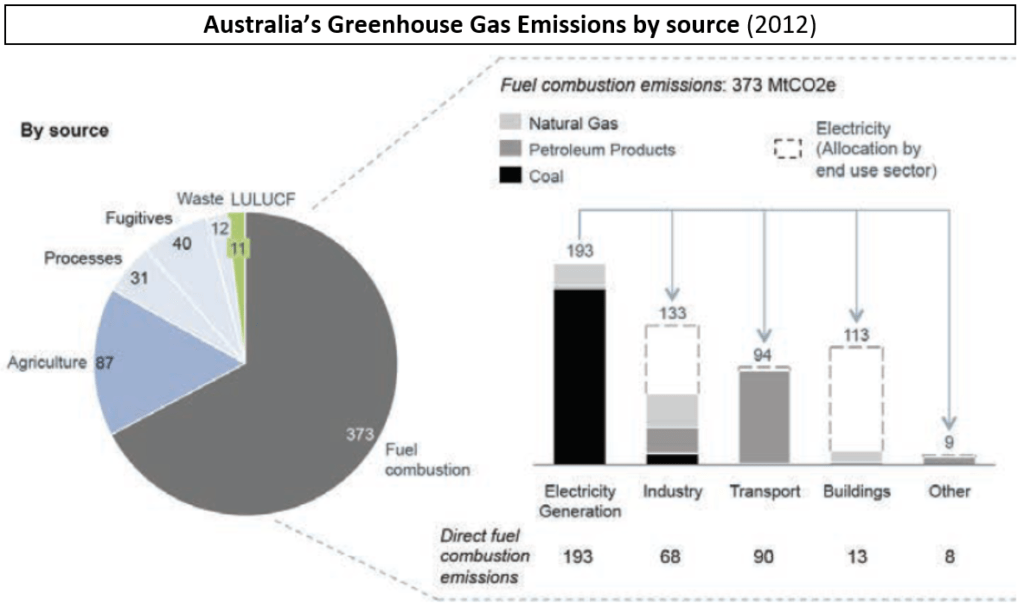

Start with the sectors that contribute the most to Australia’s greenhouse emissions. Target the following sectors: electricity, stationary energy, transport and agriculture. While the below analysis is based on somewhat outdated data , it illustrates how fossil fuels (coal, petrol and natural gas) are the source of fuel combustion emissions for electricity, industry & buildings (stationary energy) and transport.

Phasing out fossil fuels is the key to decarbonsation.

Source: Pathways to Deep Decarbonisation, Climate Works Australia, ANU (2014).

The economic recovery from COVID-19 is an opportunity to invest in the energy transition and decarbonise the economy:

- Modernise and decarbonise the electricity grid

- Policy certainty is key: introduce a carbon tax (details below) and support energy reliability;

- Fund upgrades to the transmission grid (in accordance with AEMO’s Integrated System Plan) to increase grid reliability as more renewable energy generation enters the system;

- Underwrite energy storage projects to further ensure grid reliability (e.g., pumped hydro, batteries and hydrogen)

- Support the Energy Security Board in its role to coordinate the post-2025 market redesign of the National Electricity Market;

- Implement a mechanism to support grid-firming generation (the “operating reserve demand curve” is the preferred option). This will stimulate private investment in energy storage, including pumped hydro and batteries;

- Introduce residential electricity prices that vary by hour (aka real-time pricing), facilitated using already available smart meters. This will allow electricity users to access cheap energy prices at times when renewables are abundant;

- Target stationary energy emissions by updating industrial and residential energy systems

- Switch all residential gas heating and cooking to electric systems by 2030;

- Invest $220m to modernise energy systems for 1,000 Australian manufacturers (as proposed by WWF & EY);

- Expand Australia’s support for green hydrogen under the existing $300m Advancing Hydrogen Fund, including participation in hydrogen electrolysis, storage and utilisation (including green steel) projects.

- Electrify the transport, freight and logistics sector

- Transition to light electric vehicles (cars, e-bikes and other small EVs) powered with green energy;

- An immediate $240m investment to electrify 500 metropolitan commuter buses (also proposed by WWF and EY);

- This will support the development of Australia’s lithium-ion manufacturing industry and position Australia to provide electric buses to local markets;

- Support hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles for material-handling, trucking and shipping where safe and appropriate.

- Promote sustainable farming and agricultural practices

- Adopt a supply-chain view of emissions from pasture to plate;

- Transition on-farm energy supply to renewable sources including wind, local PV (solar)+storage or biomass;

- Reduce carbon emissions due to land clearing, potentially reaching net negative emissions through reforestation, seagrass, and other initiatives

- Localise food processing to minimise transportation and food waste (with the added benefit of enhancing local economic outcomes)

For more details on how we plan to drive emissions reductions across these sectors, please refer to our Energy & Infrastructure and Sustainable Agriculture platforms.

4. Price carbon for a carbon-constrained world

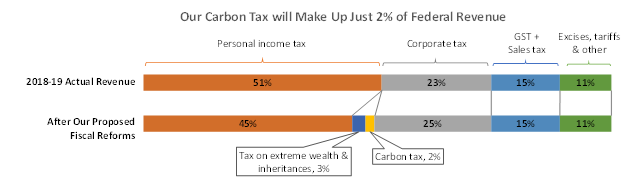

We propose to implement a carbon tax of $30/tonne, with the price to increase in line with carbon prices adopted by Australia’s key trade partners.

This would raise over $10 billion per year, funding income tax cuts that will assist those affected by short-term price impacts and fund investment in transforming the electricity grid.

Note: Based on total 2018-19 federal government revenue of $456 billion.

For more details on how we plan to reform the tax system, see our economic platform.

The world has changed, global carbon pricing is here

Recent progress shows there is growing momentum for carbon pricing at a global level, following announced commitments by major economies. This concept of countries agreeing to iterative and progressively more ambitious commitments toward climate goals has been explained by Nobel Prize-winning economist William Nordhaus in what he calls ‘Climate Clubs’.

Critics of carbon pricing, such as Tony Abbott, argued that it would make Australia less competitive. Notwithstanding the extreme short-sightedness of this thinking, the geopolitical situation with respect to climate change has changed since 2014. The EU is moving to implement a carbon border adjustment mechanism, which will mean Australia will be penalised for not having a carbon price.

Energy policy certainty will stimulate investment

There is broad consensus among economists that a price on carbon is the most efficient way to ‘internalise’ the cost of carbon, ensuring that businesses are incentivised to decarbonise. A carbon price is technology-agnostic, meaning it does not require government to make bets on what are the best low-emissions technologies (something the Morrison Government is doing with its Technology Investment Roadmap).

A carbon tax it will create a price signal that will allow the market to decide the least cost pathway to decarbonisation across all sectors of the economy.

A carbon tax and an emissions-trading scheme (ETS) are both ways of implementing a price on carbon. A carbon tax sets a price and then lets the market determine the quantity of carbon emissions, while an ETS sets the quantity (cap) and then lets the market determine the price (trade). A carbon tax is preferred by business because it provides industry firms with a fixed price, allowing businesses to make informed budgeting and investment decisions.

Price certainty under a carbon tax is especially critical for investment in electricity assets like energy generation/storage and transmission lines. The lack of a coherent energy policy under successive Liberal/National governments has driven underinvestment in energy generation assets, driving up energy prices. A carbon price will be the backbone of a consistent and long-term energy policy for Australia and support the positive contributions made by individual Australian states and industries.

5. Continuing to subsidise fossil fuels is a losing economic strategy

The IMF has reported that Australia provided US$44 billion in energy subsidies in 2021.

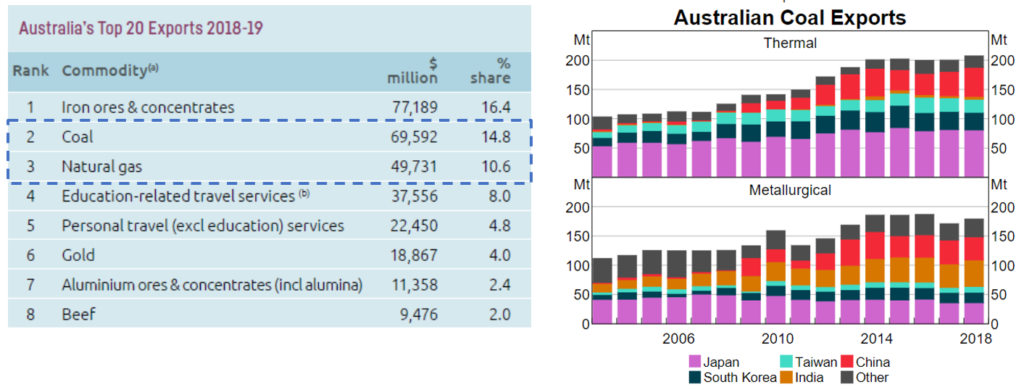

Coal and natural gas are Australia’s second and third largest exports, together making up more than a quarter of all exports. Yet the market for fossil fuel exports is changing rapidly in response to net-zero commitments by key trading partners. It is both a moral and economic imperative that Australia stops subsidising our fossil fuel export industries and begins a clean transition.

Japan, our biggest export destination for coal, will be phasing out the use of coal as it moves to meet its net-zero target. China and South Korea, the second and fourth largest export destinations, have also announced net-zero targets (in 2060 and 2050 respectively) and will reduce their demand over the next decade.

The outlook for coal exports is highly uncertain, yet the government appears content to continue business as usual, pretending nothing is going on. And this is before we consider China throwing its weight around by halting the importation of Australian coal, as it has done unofficially since October 2020.

Source (top 20 exports): Australian Trade and Investment at a Glance, DFAT, 2020. Source (coal exports): Reserve Bank of Australia.

Australia can try to sell its excess coal to other buyers, namely India, as it has done during the Chinese embargo, but this market will only last so long. India will face growing international pressure to reduce its reliance on coal and join global cooperation on combatting climate.

Global coal demand is in decline. The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts global coal demand to fall by between 10% and 55% from 2019 to 2040 (World Energy Outlook 2021). The larger 55% decline is in the IEA’s “Sustainable Development Scenario” which also predicts declining global demand for natural gas.

With the announcements of net-zero emissions targets by multiple countries over the last year, there is evidence to suggest a rapid decline use. Whilst it is not possible to say where in the range of IEA’s forecasts coal will go, it is absurd that the government continues to subsidise coal mining and gas extraction activities for export. Any such funds applied to the sector should only be for the purpose of moving it towards harm minimisation, with the carbon credits system being the determinant of value realised.

6. Keeping communities whole through the energy transition

The energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables will leave many people and communities behind unless there is orderly planning, interventions, and pathways for those currently working in these sectors.

The fossil fuel sector has donated $ millions to political parties, successfully stalling its demise by persuading the Federal Government to prop up coal, gas, and oil with $ billions in handouts for new gas-fired power generation, new coal mines, and petroleum refining.

This flies in the face of what is the inevitable closure of coal and gas-fired power generation, an end to coal and gas exports and a shift from petroleum and diesel to electric powered transport.

Robyn Denholm, the Australian Chair of Tesla, has noted that the market opportunity for lithium-ion batteries is 8 times Australia’s coal exports in 2020. It’s high time the government stopped flogging the dead horse of fossil fuels and started supporting the green transition.

The transition has already started now that renewable energy costs less than fossil fuel based energy. However, there is no plan for, or investment in, the transition, and no consideration for the current workforce (and their families) in coal, gas, and petroleum-related industries. Nor is there a plan for the many associated businesses such as the 6,000 fossil fuel service stations around the country.

We propose a Just Transition Authority charged with planning the transition, fostering job creation where it is needed, and managing the economic impacts as opportunities evolve. It should, for instance:

- Ensure workers are provided advanced notice of plant and mine closures

- Support workers in transition pathways to find new jobs (that align with Australia’s Economy of the Future)

- Provide technical education and training to support advanced manufacturing applications in for instance:

- Software and design

- Robotics

- Machine learning

- Focus on industries that leverage Australia’s world’s best renewable power resources (particularly activities that have the flexibility to use electricity at times of high renewable output, e.g. on sunny/windy days)

- Cleantech:

- Green hydrogen,

- Hydrogen fuel cell EVs,

- Green steel,

- Lithium battery production

7. No to nuclear power

While it may be possible to build a safe domestic nuclear energy program it would not be economic and will be too slow to roll out. Nuclear energy could take 20 years to establish. Renewable energy is much easier and cheaper to add to the energy grid and we already have ample experience with renewables. South Australia shows what is feasible – it now sources over 60% of it’s electricity from renewables.

Note that we support continued operation of the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation research reactor at Lucas Heights. This reactor is vital for research and nuclear medicine in Australia.

See also our posts on nuclear submarines and nuclear power.